Kyrie Irving was a natural.

At basketball, of course—that was obvious before he got to high school—but at acting, too. The No. 1 draft pick discovered this during his rookie NBA season in Cleveland in 2012, when he earned an endorsement deal with Pepsi that would grow into something bigger, and weirder, than he or the soda giant could have imagined.

Irving's first work for Pepsi, created by its longtime content agency Davie Brown Entertainment, was a goofy but charming 80-second Pepsi MAX video around the 2012 Super Bowl, in which Irving showed what he would do if he won Pepsi MAX for life. But it was their next project together, "Uncle Drew," a comic foray into longer-form content, that was destined to become a multiyear success story.

The premise was ridiculous but amusing: Irving, done up in heavy makeup and prosthetics to look like an old man (in fact, he was barely 20 at the time), schooled some baffled youngsters at a pickup game, with cameras rolling.

See Chapter 1 of the saga here:

The five-minute clip was immensely fun to watch and an immediate viral smash—one of the big early successes of prank advertising. It has since clocked more than 52 million views on YouTube and spawned a number of sequels over the next five years.

But fast-forward to 2018 for the plot's most unlikely twist.

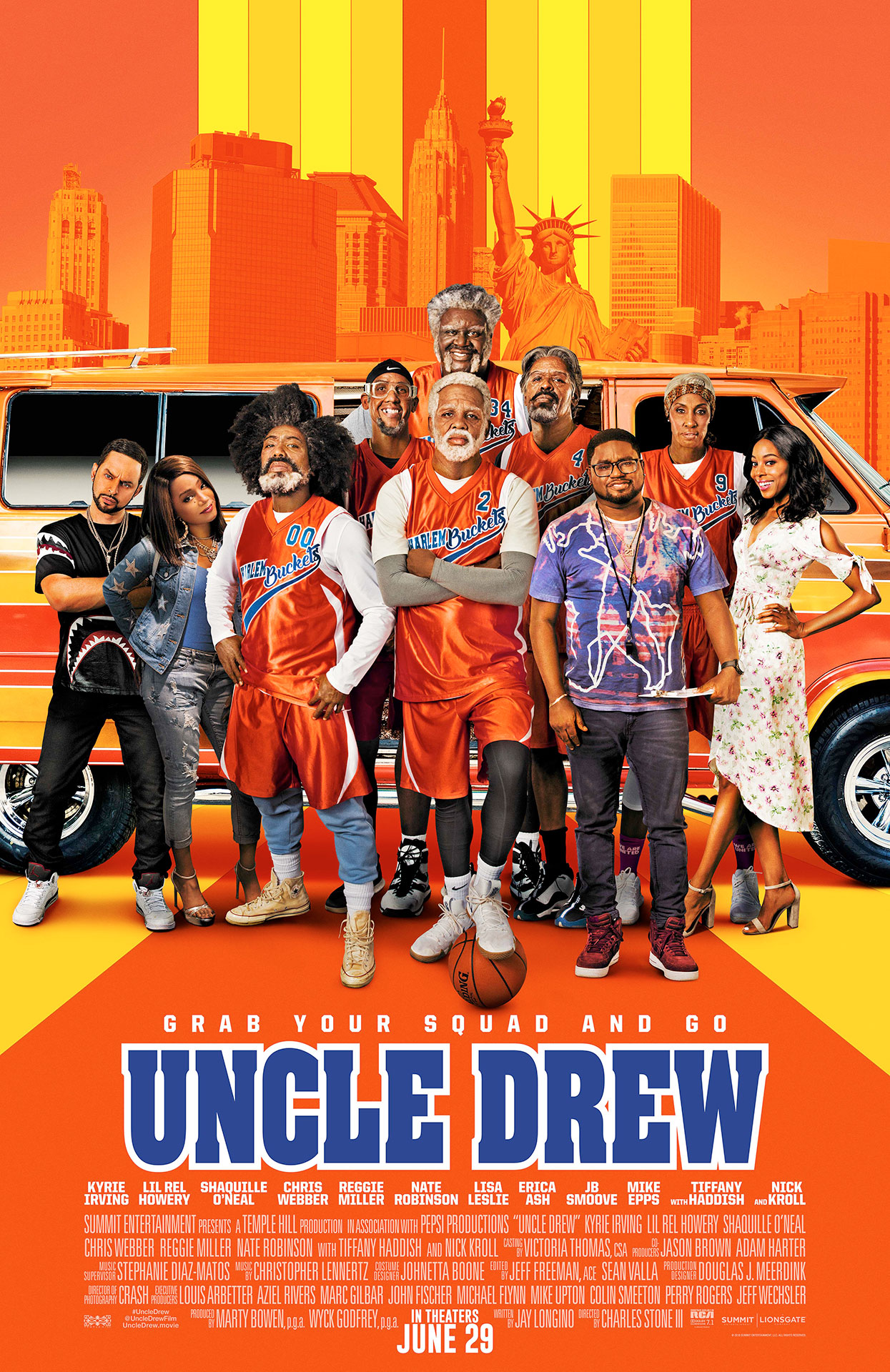

Against all odds, Uncle Drew made his biggest leap yet—into feature films. Uncle Drew, the movie, hit theaters June 29 and enjoyed strong box-office numbers and decent (if not quite spectacular) reviews. It's the first true brand campaign to make such a jump, even though Burger King and some other brands have promised features in the past.

Here's the Uncle Drew trailer:

The Uncle Drew story is a fun one on many levels, offering plenty of lessons for marketers and creatives about content, talent and the evolution of branded entertainment—including, of course, working with Hollywood.

Here's how it all went down.

Up for anything

"This young kid, Kyrie, was so charming, so up for anything," recalls Lou Arbetter, who was Pepsi MAX's brand manager back in 2012 (and is now general manager of the PepsiCo Content Studio, heading up all in-house content creation).

Arbetter was impressed by Irving's "Pepsi MAX for life" video, particularly since Kyrie had filled in at the last minute for another athlete who had canceled.

"There's one scene in there where he gets into a tub full of ice, with Pepsi MAXes floating in there," Arbetter says. "I remember seeing that and I was like, 'Wow, this guy is comfortable in his own skin and brave enough to try cool stuff.' That's when I said, 'Guys, we've got to sign him.'"

Pepsi signed Irving to a two-year deal, and Davie Brown was tasked with coming up with his next project. Luckily, Marc Gilbar, a creative director at Davie Brown (he is now executive creative director at Farm League), had an idea he'd been kicking around for a few months—of dressing an NBA player in old-man prosthetics and taking him to a pickup basketball game.

"It felt like it'd be a fun wish-fulfillment fantasy for your everyday weekend warrior to play pickup basketball against an NBA player," Gilbar tells Muse.

There was certainly a burgeoning appetite for this kind of prank content at the time, but there was also a major potential stumbling block.

"I'd done research about what it would take to put someone through that type of prosthetics, and it was three to five hours," Gilbar recalls. "All of the athletes we had worked with up to that point, you get half an hour, an hour tops."

Still, Gilbar figured it couldn't hurt to ask Irving's agent, Jeff Wechsler.

"I kind of threw out in passing, 'Do you think we could ever get Kyrie for an 8-, 10-, 12-hour day, and he'd sit through this intensive makeup process?'" Gilbar recalls. "And Jeff said yes. He thought it sounded cool."

Indeed, Irving really was up for anything.

Bill Russell meets Morgan Freeman

"Uncle Drew," which had the original working title "Old Man Irving," was really brought to life by a triumvirate of talent, according to Gilbar—Irving, who truly embraced the character and developed his personality; makeup artist Ed French, who largely came up with the character's look; and director Jonathan Klein, who worked with Gilbar on the big picture of the project, including how the video would be shot.

"Jonathan and I always saw Drew as Bill Russell meets Morgan Freeman," says Gilbar. "Kind of this old, wise basketball player who yearns for how the game used to be played and has some resentment for where it's gone."

The night before the April 2012 shoot, Gilbar and Klein met with Irving at his childhood home in New Jersey, just down the road from the Clarks Pond basketball court in Bloomfield, where they they would shoot the following evening.

Klein showed Irving some of Eddie Murphy's old Saturday Night Live sketches and explained to him how prosthetics can change a character, and how Murphy wouldn't just talk differently but move differently when he was playing a different person.

"I think it really clicked for him, and it was going to be up to him to define who this guy was," says Gilbar.

Irving could draw from his own life, too. He was very close to his father Drederick—who had played college ball at Boston University under Rick Pitino, and professionally in Australia—and would observe how he talked about and played the game. This helped form Drew's old-school philosophy.

Sitting in the makeup chair for the first time, Irving had four hours to look in the mirror and try out material.

"The first time he got up out of the chair, he was already moving much more slowly," Gilbar recalls. "He would go up to his dad—and he's now miraculously older than his dad—and start talking to his dad the way his dad talked to him. It was pretty funny to watch."

The shoot

Hidden cameras were popular at the time, but Klein wanted a more cinematic look. So, to explain the presence of high-end cameras at the court, the crew said they were shooting a documentary about a different player, Kevin (played by a childhood friend of Irving's). Within this fiction, Drew was Kevin's uncle. (The name Drew came from Irving's middle name, Andrew.)

"While Kyrie was in makeup, we had our camera crews already at the court, filming for a couple of hours," says Gilbar. "The people got comfortable with the cameras and didn't feel particularly weird about it."

Klein also decided he wanted to shoot at night.

"It really helped shape the tone of the piece," says Gilbar. "It gave it this sort of Field of Dreams magic to it. The old man comes out at night and can play like he's 25 again."

After the video came out, some viewers assumed the whole thing had been staged, since a lot of the bystanders are seen drinking Pepsi. Not so, says Gilbar.

"To Pepsi's credit, they never felt like we needed to be too heavy-handed with the product," he says. "But what we did do was put a couple of barrel coolers of Pepsi MAX on the outside of the court. It was a warm night, and they were free, so people naturally started drinking it. In some places it may have felt like it was placed there, and it was, but the people weren't acting."

A mission from God

Even before the video rolled out, Pepsi felt it had a hit.

"There are times when you see something and you're like, 'Oh, yeah, we got gold,'" says Arbetter. "We had a little media planned, but we were curious whether we would even need much. And we didn't. We knew it was good, and it was really fun to see it blow up and for fans to start sharing it like crazy."

With a hit on their hands, Arbetter naturally urged Gilbar and the Davie Brown team to expand the Uncle Drew universe for a follow-up.

"It really became a world we were building," says Gilbar. "That's when we started to think about it more like, 'Who is this character? What is his backstory? Who did he play with growing up, and what is his mission? What is he doing? What drives him?'"

For the sequels, they took inspiration from The Blues Brothers in particular, and they set Drew on a mission to get his old team back together, like Jake and Elwood getting the band back together.

"In The Blues Brothers movie, they were on a mission from God," says Arbetter. "So the first person Drew met with in Chapter 2 was Bill Russell, who is as close to a basketball deity as as you can get. So he started to get his team back together, to educate the youngbloods on how the game should be played."

That story arc already started to feel a bit like a movie—indeed, it was influenced by one directly. And in fact, it was these "Uncle Drew" chapters that caught the eye of an executive at Temple Hill Entertainment, John Fischer—and soon, his colleague Marty Bowen—who eventually became convinced they could bring the material to the big screen.

Uncle Drew, the movie

Still, it was far from clear whether that was possible.

"It was such a far-fetched notion to think there could be a movie. I don't think anyone on the agency or Pepsi team ever thought that was a possibility," says Gilbar.

The Temple Hill execs begged to differ. Initially, it was suggested that Irving write and direct an Uncle Drew movie himself, since he had been listed as writer and director on the shorts. This idea was ditched when it became clear that Klein, who had really directed them, had selflessly ceded credit to Irving to make the shorts seem that much more intriguing. (To be fair, Irving did improvise a lot of dialogue and blocked out a lot of scenes, earning at least a share of those credits.)

Before long, all of the parties involved—Temple Hill, Pepsi, Davie Brown and Irving's agents—got in a room to hash out how a movie could actually work. Over a span of more than a year, a plan slowly came together.

Pepsi felt that Bowen and the Temple Hill team had a true love of basketball, so they were comfortable moving forward and agreed to fund the writing of a script—a job that went to Jay Longino (who had written Skiptrace with Jackie Chan and Johnny Knoxville). Meanwhile, Charles Stone III (see below, on set with Irving), best known for writing and directing the old "Whassup" ads for Budweiser, was tapped as director. (Summit Entertainment and Pepsi Productions also produced the film with Temple Hill, and Lionsgate distributed it.)

Photos by Quantrell Colbert

Clearly, in order to work, the movie had to depart significantly from the ad campaign.

"As a feature comedy, it's much brighter and broader," says Gilbar. "There's some of the same characters, but Uncle Drew is not the lead. He's sort of the second lead, which I thought was smart. It's a lot to ask Kyrie to do, so they brought in a more experienced comedic actor [Lil Rel Howery, from Get Out fame] to be the main character."

The plot is similar to the shorts in one key respect—it features Drew traveling around and getting a team back together, this time to play in the Rucker Classic (based on a real annual event at Rucker Park in New York City). Howery plays the team's coach, who is looking for victory to vanquish a painful memory from his youth.

Crucially, though, the producers weren't looking at the material as an extension of an ad campaign. They just wanted to tell a good story.

"It always comes down to character and to writing," says Arbetter. "This has all the usual attributes of a classic story you can watch for longer than 30 seconds. Jay Longino is a fantastic writer. He loves the game of basketball. We were focusing first and foremost on entertainment, on creating a story people would actually want to see. That was really the only lens."

Athletes as actors

In the end, reviews of Uncle Drew have been positive (66 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, a 57 on Metacritic) less because of the script—some have complained the story is overly formulaic—and more because of the athlete/actors' performances in it.

And they are amusing indeed, by Irving as Uncle Drew, of course, but also by Shaquille O'Neal, Chris Webber, Reggie Miller, Lisa Leslie and Nate Robinson as his teammates. (The cast is rounded out by professional actors including Erica Ash, J.B. Smoove, Tiffany Haddish and Nick Kroll.)

Swipe through some of the character shots here:

It wasn't hard to get the NBA pros involved. The whole Uncle Drew campaign has a kind of "This Is SportsCenter" appeal to it—everyone seems to want to be in it.

"There's a funny anecdote about Nate that I'm not sure has been written about," says Gilbar. "When we were casting Uncle Drew [Chapter] 3, Kyrie told us a story where he was playing in an NBA game in Chicago. Nate Robinson was on the Bulls at the time. Kyrie was at the free-throw line, and he makes the first free throw. And Nate, who's on the opposing team, comes up to him and says, 'Yo, Kyrie. I love the Uncle Drew series. You've got to put me in the next chapter!" And then walks back to his line. And Kyrie is like, 'What!? Did that just happen?'"

They immediately signed Robinson up for Chapter 3.

"He's really funny, and his size [5-foot-9] makes for a great sight gag if he dunks," Gilbar says of Robinson. "So we threw him in there, and we were thrilled to see he made the film as well, because he's such a unique talent."

Gilbar has a few theories about why the athletes are able to deliver such strong performances in the Uncle Drew series.

"The thing about Uncle Drew that I think is fun—the players get to play a part in creating their own characters, both on the page but also just talking about what they're going to look like, what their name is going to be, what they'll wear," he says. "It's fun to dress up and play a character. And also, it's easier for a first-time actor to create a character, I think, when you're wearing a mask—or so I'm told. And of course, you also get to go out on the court and show off, and that's always fun as well."

Nobody's chugging a Pepsi

A big question that had to be resolved for the movie was how heavily to include the Pepsi brand. In the end, Arbetter says, restraint was the order of the day. Aside from the Pepsi Productions name in the opening credits, and some Pepsi signage in the Rucker Park scenes, the brand remains largely in the background.

"People's B.S. detectors are so attuned now," Arbetter says. "Nobody wants to be marketed to. We really needed to entertain first, and if people leave the theater smiling and feeling like, 'Alright, that was a good time and worth the money,' then the brand gets credit."

"I agreed with Pepsi that you shouldn't try to make it a commercial," adds Gilbar. "The success of the thing is really in its entertainment value, and that consumers would ultimately see the connection to Pepsi. You don't need to see a drink shot in the film for it to be a success."

Swipe through more shots of Drew:

So, how successful will the movie be for Pepsi? As of this writing, it's made more than $30 million domestically at the box office, versus a reported production cost of $20 million—giving Pepsi a nice little financial boost. But of course, that's just part of the story. The larger effect on the brand is harder to gauge.

"It's a good question because we have discussions about it," Arbetter says. "This is a big brand and a big business. The [box-office] dollars are nice, but the brand itself is worth a lot more. If Pepsi is in pop culture—like we've been for years, but in a different, new and fresh way—that builds the equity of the brand in an authentic way that I don't think we could have done otherwise. So there's value here, beyond simple box office, that might be a little difficult to quantify in the short term. But the company is forward-thinking enough to say, 'We see there's value here. We made people smile over the [July 4] holiday weekend.' And the brand gets a lot of credit for that."

"Advertising is really an inexact science," Gilbar adds. "It's hard to know why someone buys a can of Pepsi. Is it about how many times they saw a Pepsi commercial? Or is it this decade-long impression of whether or not the brand is a brand you like? Does the brand do things you can relate to, or tell stories that move you?"

He adds: "I think ultimately, if the movie Uncle Drew succeeds, or people like the character, then somewhere, subconsciously, they give Pepsi credit for it. And that may manifest in buying a Pepsi product at some point. Marketers will increasingly have to understand that in a world where consumers aren't watching live television, and aren't seeing as many 30-second spots with product shots, it's about a long-term play where you have to win over an audience and build trust with them and an affinity that will manifest itself in sales somewhere down the road."

Jumping on the bandwagon

Given the success of Uncle Drew, should we expect Geico: The Movie and A Snickers Story coming soon to a theater near you?

"I think it'll be really interesting to see," says Gilbar. "This is a good test case. It really did start as a branding campaign, and I think it's certainly possible. It sets the stage for it, which I'm not opposed to."

"I do think a lot of folks are recognizing there's an opportunity in telling really compelling stories," adds Arbetter. "But the first lens has to be entertainment. It has to be worth people's time—and if it's a movie, worth their money. If you don't make it worth their time and money, then it's a dangerous endeavor."

Swipe through a bunch of posters from the ad campaign below: