Medical illustration is one of the purest meldings of art and science. Visualizing how the human body works has been a challenge literally for millennia. From ancient Egypt, where medicine was essentially invented, through the works of Leonardo and Michaelangelo during the Renaissance, medical illustration has been essential to humanity's understanding of itself.

One of the most celebrated medical illustrators of today, Cynthia Turner, continues that hallowed traditional in impressive fashion. Her beautifully imagined and executed works, dramatically colorful with striking visuals and a clarity of message, are celebrated across the medical world—where they're used in everything from ad campaigns to medical conference exhibitions to event and print collateral.

In 2014, Turner received the 2014 Brödel Award for Excellence in Education from the Association of Medical Illustrators for her "outstanding educational contributions to the profession of medical illustration." In 2019, she was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award from AMI for "extraordinary lifelong contributions to the advancements of medical illustration and scientific knowledge."

Being a medical illustrator requires a remarkable combination of scientific knowledge and artistic skill. We spoke to Turner about the profession, her own career and creative process, and some of her favorite illustrations she's done over the years.

Muse: What is your history as an artist, and how did you get involved in medical illustration?

Cynthia Turner: I was always inclined to draw what I see, and to create representational art or conceptual art, but not abstracted art. I also knew from an early age I wanted to make a living as an artist. There didn't seem to be much room for someone like me in fine art, so when I went to school, I pursued a BFA in advertising design and illustration. While I was in the midst of my studies, my design advisor sent me to see a medical illustrator who had just arrived on campus. He thought that might appeal to me—and he was right! The moment I saw my first medical illustrations, I knew that was the place for me, and that there was a real niche for my artistic representative inclinations. This medical illustrator became my first mentor. I began taking independent studies under him and later interned with him while I completed my BFA degree.

Medical illustrators gain their formal training in a graduate program associated with a medical school. With his advice and guidance, I began preparing for graduate school, adding pre-med courses to my BFA curricula. I actually had believed I didn't like science, until it suddenly became very meaningful to my artistic pursuits. I received my MA in biomedical communications at the University of Texas Health Science Center, also known as Southwestern Medical School, in Dallas.

Medical illustrators stay current by board certification. Every five years, board certification is renewed by completing the requisite credits through continuing medical education, and by staying abreast of the curve of evolving visualization software. I have been in a partnership with another medical illustrator for over 30 years. He is also my husband! Our studio is Alexander & Turner Inc. My agent is the marvelous Gail Thurm, senior vp of pharmaceutical services at Shannon Associates.

What appeals to you about doing art in the medical industry? Is it the intricate nature of the subject matter that you find beautiful?

Yes, the subject matter is indeed beautiful. The divine architecture, the wonders of the human body and how it works—or how it fails—and the rapid pace of medical advancement in our lifetimes have made it a wild ride constantly full of stimulation. I trained to draw anatomy and surgical illustration. Now I also do a lot of work at the cellular and molecular level. It is the great cosmic zoom—inner landscapes can look like intergalactic landscapes.

Medical illustration has been around for a very long time. Its roots can be traced back at least 2,000 years to Hellenic Alexandria around the 4th century BC. Hellenic illustration was created on individual sheets of papyrus, and portrayed anatomy, surgery, obstetrics and medicinal plants. The Renaissance gave us Leonardo da Vinci, the first medical illustrator in the contemporary sense. Leonardo dissected and studied from life with his insatiable curiosity. He pursued his own anatomy book, and pioneered the use of cross sections and exploded views. Leonardo's 800 anatomical drawings remained unpublished until the 1800s. Michelangelo, Leonardo's contemporary and his rival, was also a student of anatomy who began with his participation in public dissections in his early teens, when he joined the court of Lorenzo de' Medici and was exposed to its physician-philosopher members. It showed in his spectacular work that captures movement and tension by his thorough understanding of musculature, tendons and skeleton. Michelangelo also worked on anatomical texts.

Medicine has always been taught visually. It is necessary for healers to understand the three-dimensional interrelationships in the body and in its ultrastructure. A lot of drug research is based on understanding or hypothesizing the ultrastructure of protein molecules in order to block receptors or enhance them. Bionics and nanotechnology is the fusing of mechanical engineering with the understanding of the structure and function of living tissue. It is an exciting time to be a medical artist. Leonardo and Michelangelo would have reveled in current science.

Can you describe your style? A lot of your illustrations feel almost like alien landscapes.

That's a tough question. I suppose I have a style. It has been described as cinematic. It is very colorful. I loved foundational design, academic drawing and color theory and composition. I always have that in mind when I visualize. I want my paintings to be interesting and engaging to look at it, even if you don't know what the subject matter is or you don't have the benefit of reading a caption that explains it. I want them to stand alone on visual impact alone. Someone once told me, "I don't know what that disease is, but it is so beautiful I wish I had it."

But that doesn't mean the message is not important. The message is everything. Medical illustrators are often called upon to visually describe complex science in a concise and understandable way. We have to be good storytellers. Sometimes we have to incorporate a timeline of unfolding events into one visual, or create a series that tells a story.

Like any good design, if it is successfully executed, it is effortless for the viewer to grasp the message. Sometimes the image will be unforgettable because it creates a visual understanding.

How long does it take you to complete a typical piece. What is your process, and how much research do you do?

Every project is different, of course. Any work I do with drug launches or a mode of action—how a drug works—is under nondisclosure agreements. There is no place to research the subject but with the researchers, inventors and innovators themselves. It has not yet been published. I am a part of the effort helping to bring their work to light. Deadlines are generally fast—a week or a little more for concept development, and about two weeks for the final art. Along the way are several rounds of review for accuracy and authenticity.

What materials do you typically use?

I began as an airbrush illustrator. Initially, I found it difficult to make the transition to digital because I had to do it on my own as a working professional, but once I started to get the hang of it, I found that I enjoyed it. I wouldn't trade my foundational education for anything. I think that the foundations taught me to see, conceptualize, draw and paint. Once you have acquired those skills, you can adapt to any medium—you just have to work on building the skills to master the new medium. I primarily work in Cinema 4D, a 3D modeling software program, and Photoshop. I also incorporate biologic data from the Protein Data Bank, a database for three-dimensional structures of large biological molecules, or from CT scan voxels—a voxel is a volumetric 3D pixel—from data captured when diagnostically scanning the human body.

What's the biggest creative challenge you usually face?

It is usually the same challenge every time: First, understand the science, then mentally design the visual message to be conveyed, then design a beautiful composition and hopefully execute an interesting, dynamic visual that successfully communicates the message. It's often referred to as visual science. It is the nature of the field to help present and teach new ideas, new discoveries and new breakthroughs through the power of visualization. Medicine itself is a visual discipline, requiring a three-dimensional understanding of the human body and its inner worlds, and it requires surgeons, doctors and researchers to be very visual in their thinking. Medical knowledge has always been taught through tremendous visual support and visual study.

Where does your work typically appear?

My work can appear as large-scale artworks for trade shows at medical conferences, to global or national campaigns for drug launches that appear in trade journals, to some editorial work.

Can you pick a few of your favorite pieces and give us the stories behind them?

I created 24 large-scale artworks for Varian Surgical Sciences' "Take a Closer Look" campaign, highlighting the ability of their precise radiological surgery technique, called Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy, to treat and cure some tumors in a few treatments with no damage to surrounding tissue. I worked with one corporate art director and two physicists on this series over a period of eight years. The physicists would explain the radiological science and the crucial points about why their treatment was innovative for various tumors in various locations in the human body, and then I would visualize it. The works appeared on trade exhibits and were also distributed as limited-edition signed prints.

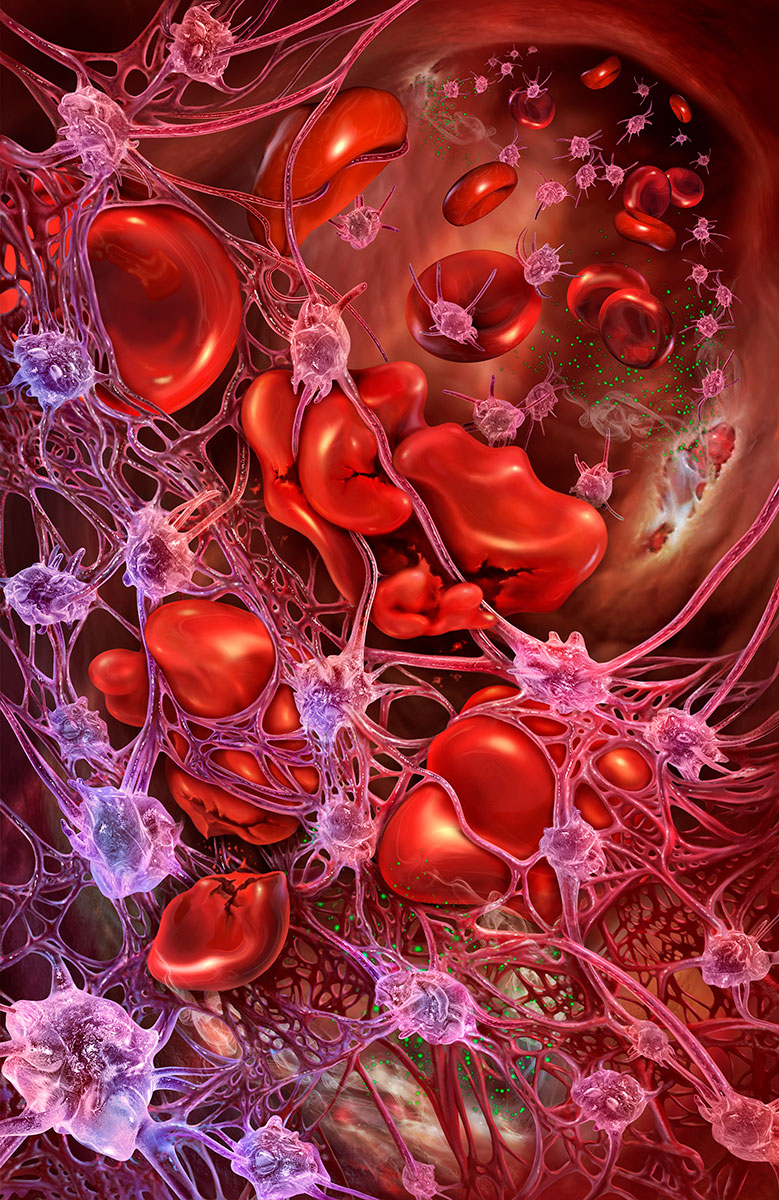

I worked with the chief researcher at Alexion Pharmaceuticals to develop visuals for his breakthough drugs to treat rare, catastrophic bleeding disorders. One of these, Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (aHUS), manifests by chronic uncontrolled complement activation leading to the continuous activation of platelets and endothelial cells—which means the body creates an uncontrolled, unstoppable clotting response, which results in sudden progressive and catastrophic failure of vital organs, including the kidney, heart and brain.

Platelets are small cells that are always circulating in the blood. They look like little flat discs. When they are activated by a biochemical alarm, they rush to a site of injury, and become spiky in form and very sticky. They cover the injury in a vessel by massing together. Another biochemical activation causes them to transform into a webbing called fibrin, that traps red blood cells and other cells circulating in the blood, forming a protective clot or thrombus at the site of injury. In aHUS, this response loses its checks and balances and becomes uncontrolled, resulting in a catastrophic cascade. The illustration depicts the platelets aggressively stretching out to form the webbing, and entrapping red blood cells and injuring them.

"Flora" is a self-promotional fantasy illustration, creating a visual pun on the idea that gastric flora might be blossoming flowers in the digestive tract. I researched the common bacteria—called flora—of the gut. I created 3D models of them, using electron micrographs for reference. I arranged the 3D-modeled bacteria to construct a flower, using different bacteria for different parts of the flower. The churning gastric juices and primordial environment of the gut comprises the environment from which the flower grows. The flower springs forth from the microvilli found in the lining of the small intestine. The flowering is depicted by petals of Bacteroidetes, Bifidobacteriam, and Enterococcus faecalis, pistils of Lactobacillus and stamens of Enterococcus faecalis perched on stalks of Escherichia coli. The flower itself emerges on stalks of Clostridium difficile. Bacillus cereus, long rod-shaped bacteria in their arthomitus stage attach by fibers to the intestinal epithelium, grow filamentously and sporulate. Creating a flower that both looked like a flower but was also easily recognized as being constructed of identifiable bacteria required a creative balance between the two.

I created another self-promotional work where I sought to create a portrait of the dramatic moment the death grip of a natural killer T (NKT) cell overcomes a cancer cell's defenses, memorializing a moment humanity desires. Cytotoxic natural killer T cells are cancer assassins that induce cancer cells to undergo programmed cell death known as apoptosis. Natural killer T cells recognize specific sites on the surface of cancer cells called antigens, bind to them, and release biochemical proteins that form pores in the cancer cell's membrane and specifically induce the cancer cell to destruct. I researched the morphology of natural killer T cells, cancer cells, and natural killer T cells and cancer cells in a death struggle, by studying electron micrographs and written research. I created 3D models of a natural killer T cell, a cancer cell, fracture explosion, and cell debris using Cinema 4D. The rest of the digital painting was completed by hand work of drawing and painting in Photoshop.

Do you work on non-medical art?

Yes, I do some drawing and painting from time to time. I would like to have more time for it.

What projects do you have coming up that you're excited about?

I've been working on a major art program for some general health warning labels for over two years. I look forward to that becoming public. It will be ubiquitous—everywhere the public looks. Most of my work is generally to the trade and not seen apart from the medical professional audience for whom it is intended, so this program will feel different to me when it is published.