There's no shortage of provocative album art—in fact, courting controversy might be an art form in itself.

Take the George Condo-designed cover of Kanye West's modern classic, "My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy." It features an armless angel straddling a demonic rendering of Ye, and whether or not it was banned—as West wished and dubiously insisted—it certainly became iconic).

To be fair, the line between authentic creative expressions that challenge cultural conventions and shock marketing tactics that generate publicity can be a fuzzy one at best. And in the glory days of physical media, stories abound of artists seeking to strike a balance between grabbing the attention of audiences without alienating the retailers upon whom they depended to stock records. The results of these dynamics are decidedly mixed.

Some historically controversial pop and rock album covers are, especially in retrospect, definitively obscene, creepy or cringey. These range from exploitative and gross in some of the worst cases (e.g. overtly sexualized prepubescent models) to maybe just bizarrely tasteless in other examples, like The Beatles' jarringly metaphorical baby meat cover (a protest against the Vietnam War, the band claimed)—for Yesterday and Today in 1966.

Plenty of covers have drawn the ire of shop owners—or governments—each in the same way, tilting over the line from suggestive to someone's definition of prurient (often by employing closeups of thinly-veiled crotches). See, for example, The Rolling Stones' Sticky Fingers running afoul of Franco's Spain in 1971; the Brazilian junta banning Gal Costa's India in 1973; record store owners rebuffing XTC's Skylarking in 1986; Walmart and Kmart refusing to carry The Black Crowes' Amorica in 1994).

Other examples race straight into pornographic territory—like Death Grips' incredibly NSFW dick pic cover for No Love Deep Web in 2012.

Where exactly the bar for controversy lies—or whether there even is one—also varies widely by genre. Extreme gore, demonic imagery and varied NSFW graphic imagery abounds in hard rock and metal marketing. Many covers seem clearly meant to incite outrage from religious groups—like a demonic mascot drowning a priest in Dio's Holy Diver (1983) or the over the top gory desecrations of Jesus in Marilyn Manson's Holy Wood (2000) or Slayer's Christ Illusion (2006). (Others go much further beyond the conventional boundaries around violence and anatomy, and after a point, start blurring together).

But even with hindsight being 20/20, other controversial album covers might seem like much ado about nothing (or maybe just a little nudity). Here are a handful of those more ambiguous cases, which have caused a public stir, executive hand-wringing, or both—for a variety of reasons.

The Mamas and the Papas

If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears (1966)

Move over Marcel Duchamp. Almost 50 years after the Dadaist artist presented "Fountain"—the artwork consisting of an out-of-context urinal—this album cover was deemed indecent by retailers for showing a toilet.

John Lennon and Yoko Ono

Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins (1968)

Adam and Eve much? Perhaps the ne plus ultra of the naked human form causing an unnecessary huff, this full frontal album probably wouldn't have raised an eyebrow in an art gallery. As a product, though, it was sold in a brown paper bag revealing only the couple's faces. That, despite the relatively platonic nature of the poses, the obviously biblical overtones, and the fact that they claimed only to be trying to emphasize the purity of their creative collaboration (admittedly not the most convincing argument).

David Bowie

Diamond Dogs (1974)

The original depiction of Bowie as a half-man half-dog, created by Belgian painter Guy Peellaert, featured a pair of canine testicles on the gatefold until record label RCA, worried about a clampdown from censors, had them airbrushed out.

Sex Pistols

Never Mind the Bollocks, Here's the Sex Pistols (1977)

A picture is worth a thousand words. The wrong word is worth an uproar. The simple text-based artwork for the lone studio album from the seminal British punk band landed Chris Seale, a Nottingham record store manager, in jail for displaying the album in the shop window and resulted in a high profile obscenity case over the use of the word "bollocks" and its precise historical meaning (with his legal fees paid by Virgin founder Richard Branson, Seale was ultimately exonerated).

Grace Jones

Island Life (1985)

Arguably the most complex case of the bunch, this iconic image of Grace Jones—created by French artist Jean-Paul Goude (Jones' romantic partner at the time)—might seem innocuous at first glance, or arguably even empowering. The picture isn't real, but actually a composite of multiple cut photographs rearranged into a montage that Goude, a white man, then painted together—creating the illusion that Jones is striking an impressive but anatomically questionable pose. Deeper readings of the history, however, reveal more sinister undertones—with Goude's body of work and use of terms like "savage aesthetics" drawing criticism for objectifying and fetishizing black women throughout his career, and for casually fanning racist stereotypes.

Another of his works featuring Jones, snarling naked on all fours in a cage over chunks of raw red meat under a sign reading "DON'T FEED THE ANIMAL" was cropped to serve as the cover of his 1982 book—excluding the sign but disturbingly titled Jungle Fever. And his internet-breaking 2014 shoot with Kim Kardashian was a recreation of another of Goude's controversial images from 1976, "Carolina Beaumont," featuring a nude black woman popping a champagne bottle in a presentation eerily reminiscent of Europe's historical treatment of African women's bodies as freak show exhibitions. For Jones' part, however, she has consistently defended Goude (with whom she has a son), and the work they did together.

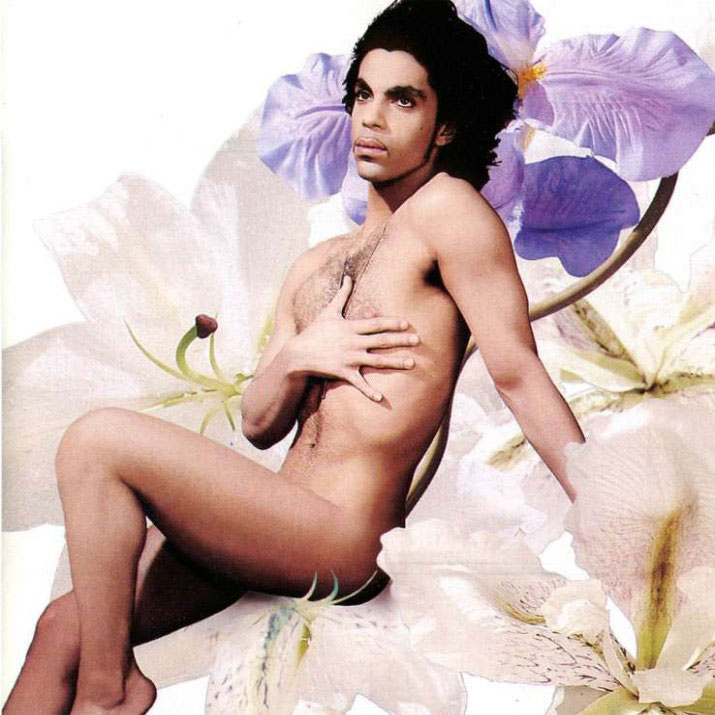

Prince

Lovesexy (1988)

Despite being a good bit more modest than Lennon and Ono's "Two Virgins," this nude image of the artist, based on a photo by Jean-Baptiste Mondino, and featuring a phallic floral organ pointed at Prince's chest, nonetheless rankled retailers, who would only sell the album wrapped in black plastic.

Nirvana

Nevermind (1991)

Oh no! A naked baby! One of the most famous album covers of all time and Nirvana's first major label release, this tongue-in-cheek critique of capitalism initially had executives at Geffen fretting over whether the infant penis would offend viewers. After pushback from Kurt Cobain, they relented in seeking an alternative. In a complicated twist, however, Spencer Elden—the four-month old baby in the image, who is now an adult—has been waging an ongoing appeals battle in court against members of the band, the photographer and the label, claiming child exploitation and that the image has irrevocably sexualized him worldwide (despite re-shooting the image as recently as 2016, this time in swim trunks, for the same $200 fee his parents were paid in 1991).

Ice Cube

Death Certificate (1991)

Despite a provocative cover featuring a corpse on a gurney wearing a toe tag that reads "Uncle Sam," this gangster rap classic was likely more controversial for the content of the album than its artwork, with Ice Cube delivering a scathing and complicated indictment of America's treatment of its black citizens while rapping about drugs and gun violence—simultaneously finding massive commercial and critical success alongside accusations of homophobia, sexism, racism against Asians and antisemitism.

Vampire Weekend

Contra (2010)

In a less politically-charged example, this emotionally ambiguous image, captured in 1983—which the band found online and licensed from photographer Tod Brody in the 2000s—became the subject of a court battle when the model featured in it, Ann Kirsten Kennis, later claimed Brody did not own the rights to the photo and it was used without her permission. (The messy dispute was ultimately settled out of court, with the band paying Kennis an undisclosed sum).

Art of the Album is a regular feature looking at the craft of album-cover design. If you'd like to write for the series, or learn more about our Clio Music program, please get in touch.